Brief Bio

I’m a Ph.D. candidate in the Population Biology Graduate Group at the University of California, Davis. Before joining the Eisen Lab, I attended undergrad at Franklin and Marshall College, then worked as a software developer in the computer industry, before returning to university and graduating from International University Bremen, in Bremen, Germany (now Constructor University), where I majored in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. I originally expected to study virus evolution or the early evolution of eukaryotes in graduate school, but was lured away to the macro side by a class on the evolution of senses. [So, I’d say the Eisen Lab moniker should be something more like, “Mainly microbes, all the time.”] I mostly work on insect vision—particularly that of adult male Strepsiptera—but have also branched out into flight kinematics to better understand strepsipteran visual requirements.

Research

|

|

|

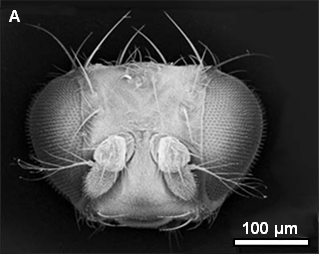

Figure 1: Comparison of the morphologically typical compound eye of a Drosophila (a true fly) with that of a Halictophagus Strepsiptera. A) Small abutting facets constitute the compound eyes of this drosopholid, each resolving a single pixel. (However, note that nearly all true flies employ “neural superposition,” in which off-axis light that would have been blocked by the recipient facet is redirected neurally (not optically) to a neighboring facet for which it is on-axis. This improves light sensitivity by about 6×, without degrading acuity at all. Because of this enhancement, flies are not an ideal reference point. However, Drosophila are extremely well-studied, and for this external assessment the comparison is sound.) B) The ‘facets’ of this Strepsiptera are clearly separated, and also much larger, because each ommatidium contains an extended retina, onto which a multi-pixel image may be projected. Because of such differences, the facets of an adult male strepsipteran’s eyes are sometimes referred to as eyelets. Notice that the ventral eyelets are much larger than the dorsal ones. This may represent a so-called acute zone of superior visual resolution; however, it may also normally scan an area from which less light is incident, so that a larger eyelet surface area is required to collect enough light in the same amount of time. (A) was taken from [2]. (B) from [3].

|

|

All this peculiarity and potential ‘extra’ visual effort invites one to ask why it occurs at all. What does an adult male Strepsiptera obtain from having such eyes? (BTW—adult females are blind, wingless, legless, and lack antennae1; but then, emerged adult males starve to death in a few hours…) How well can they see? How did their eyes evolve and why has this eye morphology been retained in Strepsiptera, while its expected enhanced acuity has not been reproduced in other insects? To address these questions I’ve been investigating Xenos peckii, a diurnal species, and Elenchus koebelei, a crepuscular species. Among many fascinating attributes, Strepsiptera are one of the few insect orders in which the same eye design is used exclusively in all three major light regimes: photopic (broad daylight), mesopic (dawn or dusk, i.e., crepuscular), and scotopic (late night). Thus, I have designs to work with a nocturnal species too. Stay tuned!

1 ^This is true of all but the most basal extant lineage in which strepsipteran females retain eyes and legs. In that single clade, adult females leave the body of their host; however, they are still severely lacking in mobility and do not oviposit. This general inability to oviposit freely has led to all strepsipteran females giving birth to live young that seek out their own hosts.

Adult male strepsipteran morphology

Surprisingly, the wings were not the source of the name of the order, or its common English name, “twisted-wing parasites”; the warped condition of the halteres was, which were then thought to be elytra, and were known to be sensors: “Strepsiptera is the term I propose by which to designate the order, which name I have given it on account of its distorted elytra” [4]. Somewhat subsequently, the halteres were thought to be twisted forewings (e.g., forewings that fail to unfold) that no longer provide meaningful lift or any sensory input, but were still considered useful for enhancing the excitatory state of the insect. Later, after dipteran halteres were better understood, strepsipteran ‘forewings’ were revisited and found to act in a similar manner. Hover over the buttons or the body parts depicted in Figure 2 below for more intriguing facts about strepsipteran morphology.

Nocturnal Strepsiptera

2 ^Some folks might want to call this (sub?)species T. mexicana; I, however, side with Dr. Cook [6], who is a taxonomist and seems to have seen enough of both to make consistent distinctions.

3 ^The family Myrmecolacidae is incredibly interesting because it consists entirely of split host infectors: male Myrmecolacidae infect ants (thus, the name of the family—most often fire ants) and females of the same species infect Orthopteroidea (most often crickets—but also mantises(!), etc.) [7,8].

Triozocera texana in flight

By carefully observing an insect fly, you can get a sense of what it can see and by extension, what it needs to be able to see. You can also obtain an indication of how fast it flies—although that can depend on what task is being attended to—which is also an important visual parameter. In general, bearers of simple eyes are either masters of vision in low-light (think spiders, most centipedes, etc.), or they have relatively slow eyes with high acuity in a limited field of view. Those with compound eyes have comparatively awful acuity, but are capable of seeing very quickly in all directions at once. However, in many ways my having photographed flying Triozocera texana is a prelude to photographing even tinier Strepsiptera, en route to strepsipteran videography, which should much more completely address strepsipteran flight capacity and its supporting optical system. (Dare I say, “Stay tuned”?) Following are some photos of T. texana freely flying in the field that I captured using a highly modified commercial insect rig. To my knowledge, these are the first still images of Strepsiptera in flight.

References

Acknowledgments

The ‘blog’ portion of this web page is written entirely in CSS and HTML (without “unfiltered_HTML”). Thanks to the following online resources for helping make this possible:

Use CSS :hover to select non-child elements

Lubna’s CSS image gallery

StackOverflow questions

CSS Tricks

For best results, this web page should currently only be viewed on desktops and laptops (i.e., no small-screened devices).

“adult males starve to death in a few hours…”

I’m making the assumption that they do not eat. If so, why do they have a mouth? Do they also have a digestive tract? Anus? Maybe these are remnants of a larval stage?

LikeLike

Hi John B.: Excellent questions! To be more precise, adult male Strepsiptera either starve to death, or dehydrate, it’s not clear which. In either case, however, they do not feed as adults. This is not uncommon in insects – particularly among males – and also occurs in mayflies, in some species of moths, etc. Adult male Strepsiptera have an incomplete digestive tract, but they do have mouths, in part because they use their specialized mandibles or mouthfield sclerite to remove the cap (cephalotheca) from their pupal case just prior to escape. Why they have other, rather poorly developed mouth parts, is a bit more involved. They are not really holdovers from larval stages – Strepsiptera undergo a complete metamorphosis, consisting of most structures being thoroughly broken down and reconstructed. Instead, it appears to be because there hasn’t been sufficient evolutionary pressure to remove them. That is, the structures aren’t known to be serving any particularly useful purpose, but then, they aren’t causing much harm either. It would probably be more problematic to remove them altogether without causing unwanted changes in other adjacent or related body parts than to leave them to slowly wither away. (“Wither,” because when mutations that degrade them but aren’t otherwise harmful do arise, they’re free to accumulate because the structures are not being used; but “slowly” because those mutations don’t provide much advantage – that is, many specimens that don’t have them are still able to survive and reproduce in very similar quantities.) So I’d say, those mouth parts aren’t leftover larval parts, but instead are evolutionary holdovers.

LikeLike

Hi Marisano, You reached out to me several years ago about vision in Phacopids, and my website on the Lochkovian (Devonian) trilobites of south central Oklahoma. I remember this now because I ran across some notes I kept, and want to know how you are doing. Also, my son has applied to the graduate school there, and is already living in Davis, auditing some classes, and hoping to be accepted. Have you found any potential links between Phacopid compound eyes and the evolution of these in the Strepsiptera? By that I mean, have you found any trends in the development of these eyes in the parasitic flies that might reasonably apply back to the trilobites by analogy?

Best of luck to you!

George Hansen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Dr. Hansen: Oh yes, “The Trilobites of Black Cat Mountain.” It has been awhile. Very nice to hear from you! Your son is here in Davis? Excellent. Which department has he applied to? I am doing well, thank you. I should update this page soon… I have recently had a publication in JEB: http://jeb.biologists.org/content/219/24/3866, so (at least) two photoreceptor classes for (diurnal) Strepsiptera. This condition they share with several beetles, their sister clade. In response to your question: Yes, I have found potential links, with interesting differences. (I wonder what you think of Schoenemann and Clarkson, 2013.) Also, I made it out to Norman, in the summer of 2014. I was seeking out a nocturnal species of Strepsiptera, Triozocera mexicana. It took awhile, but I did learn how to catch males live there. Thank you, and good luck to your son too! Cheers, Marisano

LikeLike