Quick post here. This paper came out a few months ago but it was not freely available so I did not write about it (it is in PNAS but was not published with the PNAS Open Option — not my choice – lead author did not choose that option and I was not really in the loop when that choice was made).

Tag: story behind the paper

Story behind the paper: from Jeremy Barr on "Bacteriophage and mucus. Two unlikely entities, or an exceptional symbiosis? "

By Jeremy J. Barr

Our recent research at The Rohwer Lab at San Diego State University investigates a new symbiosis formed between bacteriophage, viruses that only infect and kill bacteria, and mucus, that slimy stuff coating your mouth, nose, lungs and gut.

Bacteriophage, or phage for short are ubiquitous throughout nature. They are found everywhere. So it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that these phage are also found within mucus. In fact, if you actually sat down and thought about the best place you would look for phage, you might have picked mucus as a great starting point. Mucus is loaded with bacteria, and like phage, is found everywhere. Almost every animal uses mucus, or a mucus-like substance, to protect its environmentally exposed epithelium from the surrounding environment. Phage in mucus is nothing novel.

But what if there were more phage in mucus? What if the phage, immotile though they may be, were actually sticking within it?

It turns out that there are more phage in mucus, over four times more phage, and this appears true across extremely divergent animal mucosa. But this apparent increase in phage could very simply be explained by increased replication due to access to increased bacterial hosts residing within mucus layers. But this assumption alone doesn’t hold up. Applying phage T4 to sterile tissue culture cells resulted in significantly more phage sticking to the cell lines that produced a mucus layer, compared to those that did not. There were no bacterial hosts for phage replication in these experiments. Yet still, more phage accumulated in mucus.

Surely the law of mass-action could explain this apparent accumulation. The more phage we apply to an aqueous external environment, the more phage will diffuse into and enter the mucus layer, being slowed in the process due to the gel-like properties, and eventually resulting in an apparent accumulation of phage in mucus. But when we removed mass-action from the equation, and simply coated mucus-macromolecules onto a surface, still more phage stuck. Our assumptions were too simple.

Phage are ingenious. They have evolved, traded, and disseminated biological solutions to almost every biological problem, whether we are aware of it or not. So in order to solve the phage-mucus quandary, we needed to look to one of the most ubiquitous and populous families of proteins found in nature: the immunoglobulin superfamily. This protein fold is so ubiquitous that it appears in almost every form of life. Within our own bodies, it is the protein that affords us immunological protection. Bacteria utilize the protein fold to adhere to each other, to surfaces, and as a form of communication. And as it would turn out, phage make an innovative use of the same protein fold to stick to mucus.

Immunoglobulin, phage and mucus, are all pervasive throughout environments. The interaction between these three entities forms a new symbiosis between phage and their animal hosts. This symbiosis contributes a previously unrecognized immune system that reduces bacterial numbers in mucus, and protects the animal host from attack. We call this symbiosis/immunity, Bacteriophage Adherence to Mucus, or BAM for short.

Our work is open access and available through PNAS .

If you would like to read further about BAM and its implications see these two commentaries by Carl Zimmer at National Geographic and by Ed Yong at Nature News

Story behind the paper: Corey Nislow on Haloferax Chromatin and eLife

Hi Jonathan, I hope this mail finds you well.

I wanted to alert you to a study from our lab that will be coming out in the inaugural issue of eLIFE.

After reading your PLoS ONE paper on the Haloferax volcanii genome (inspiration #1) I ordered the critter, prepared nucleosomes and RNA and we went mapping. Without a student to burden, I actually had to do some work…

Anyhow, we found that the genome-wide pattern of nucleosome occupancy and its relation to gene expression was remarkably yeast like. Unsure of where to send the story, we rolled the dice with the new open access journal eLIFE (inspiration #2) and the experience was awesome. I’m quite keen to pursue generating a barcoded deletion set for Hfx.

here’s the paper (coming out Dec. 10) if you’re curious.

And a PDF of the paper was attached.

And I wrote back quickly in my typically elegant manner:

completely awesome

But then I thought better of it and wrote again

So – can I con you into writing a guest post for my blog about the story behind this paper? Or if you are writing a description somewhere else I would love to share it

And he said, well, yes. And with a little back and forth, he wrote up the post that it below. Go halophiles. Go Haloferax. Go open access. Go science.

My group first became interested in understanding the global organization of chromatin in early 2005 when Lars Steinmetz (now program leader at the EMBL) led a team effort at the Stanford Genome Center to design a state-of-the-art whole genome tiling microarray for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These were heady times at Ron Davis’ Genome Technology shop and the array was another triumph of technology and teamwork. The array has over 7 million exceedingly small (5 µm²). The history of how this microarray transformed our understanding of the transcriptome began in 2006. As Lars’ group dug deeper, the extent of antisense transcription and its role in the regulation of expression became clear.

The availability of this array and its potential for asking interesting questions inspired me to convince William Lee, a new graduate student in my group (now at Memorial Sloan-Kettering) to embark on a seemingly simple experiment. The idea was to ask if we could use the classic micrococcal nuclease assay to define nucleosome positioning on a DNA template. But rather than using a short stretch of DNA that could be assessed by radioactive end-labeling and slab gel analysis, we decided the time was right to go “full-genome”. Accordingly, the template was all ~12.5mB of the yeast genome. Will systematically worked out conditions appropriate for hybridization, wrote the software to extract signal off the array (we were flying blind as the array did not come with an instruction manual) and producing an output that was compatible with the genome browsers of the time. Will’s computational background proved critical here (and at several later stages of the project). The result of this experiment was a map of the yeast genome with each of its approximately 70,000 nucleosome’s charted with respect to their occupancy (the length of time that the nucleosomes spend in contact with the DNA) and positioning (the location of a particular nucleosome relative to specific sequence coordinates) in a logarithmically growing population of cells (the paper). Both occupancy and positioning regulate access of most trans-acting factors for all DNA transactions. Working with my new colleague Tim Hughes at the University of Toronto, we began to mine this data focusing first on how the diverse occupancy patterns correlated with aspects of transcription, e.g. the presence of transcription factor binding sites, the level of expression of particular genes, and the like. With this data for the entire genome, we could systematically correlate nucleosome positioning/occupancy with functional elements, sequence logos and structural features. Des Tillo, a graduate student in Tim’s lab and now a research fellow with Eran Segal, was able to build a model that could predict nucleosome occupancy. The correlation (R=0.45) was not great but it was miles better than anything that existed at the time. Tim and Eran’s labs, work with Jason Lieb and Jonathan Widom, refined the model to greater accuracy 2009 model.

Our original study (essentially a control experiment to define the benchmark nucleosome map in yeast) has been widely cited- many of these cites have come from what were two opposing camps, the sequence advocates and the trans-acting proponents. The sequence folks posed that nucleosome position is directed by the underlying sequence information while the trans-acting folks see chromatin remodelers as having the primary role. Having last worked on chromatin in 1995 as a postdoc in Lorraine Pillus’ lab (cloning yeast SET1), it has been a scientific treat to be both a participant and observer in this most recent renaissance of chromatin glory.

The protocol

As a reminder, the micrococcal nuclease (MNase) assay relies on the preference of this nuclease to digest linker DNA. By chemically crosslinking histones to DNA with formaldehyde, digesting with MNase, then reversing the crosslinks and deproteinizing the DNA, you obtain 2 populations of DNAs, those protected by digestion (and presumably wrapped around nucleosomes in vivo) and a control sample that is crosslinked but not digested (genomic DNA). The former sample becomes the numerator and the latter the denominator and you take the ration between the two. Initially we compared the microarray signal intensities, now next generation sequence counts are used to define nucleosomal DNA. This cartoon depicts the array based assay, but simply swap in an NGS library step for the arrays to upgrade to the current state-of-the-art.

So that brings me to the paper I’d like to highlight today, which asks the question: if (and how) chromatin is organized in the archae, and further, is there any correlation of archae chromatin architecture to gene expression?

My extreme background

Just like the universal fascination of kids with dinosaurs, I was captivated by the discovery of life in extreme environments like boiling water or in acid that could melt flesh on contact. Teaching intro bio, I would try to provoke the students by claiming that discovering extraterrestrial life will be a letdown compared to what we can find on earth. So while my students were occupied with classifying yeast nucleosome and transcriptome profiles in different mutants and drug conditions, I had the rare opportunity to indulge my curiosity. Jonathan E’s talks on the dearth of information on microbes, combined with my re-discovery of the early papers from Reeve and Sandman (see review) had me hooked. Reading the literature was like discovering the existence of a parallel chromatin universe. Archae histone complexes were tetramers (as opposed to the octamers of eukaryotic nucleosome core particles) but most everything else was similar- they wrapped DNA (60-80 bases compared to 147 for yeast) and although archael histones did not share primary sequence similarity to eukaryotic nucleosomes, at the structural level they resembled histone H3 and H4 in eukaryotes.

Working from ignorance

Choosing the particular archaeon to study was dictated by one criterion, the ability to grow it in the lab easily without resorting to anaerobic conditions or similar calisthenics. Again, I was fortunate in that the halophilic arcaeon Haloferax volcanii fit the bill, but more importantly, there was a wealth of literature on this critter, including a well-annoted genome (thanks again Jonathan!) and an impressive armamentarium of genomic tools. Indeed the work of Allers, Mevarech and Lloyd and others have established Hfx. volcanii as a bona fide model organism with excellent transformation gene deletion gene tagging and gene expression tools.

Home for Haloferax volcanii.

|

| This photograph shows salt pillars that form in the dead sea which borders Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank to the west. The salt concentration in the water can exceed 5M! |

So cool, now all we had to do was prepare nucleosomal DNA and RNA from Haloferax, sequence the samples, build a map and see where it led us. With everyone in the lab otherwise occupied, I tried to grow these critters. At first I was convinced I’d been out of the lab too long as nothing grew. Actually I just needed to be a little patient. Then the first cell pellets were so snotty that I aspirated them into oblivion. Finally, I had plenty of pellets and my talented yeast nucleosome group adapted their protocols such that we got nice nucleosome ladders.

This was a pleasant surprise and one we did not take for granted given the high CG content of the genome (65%). We then turned to isolating RNA. Without polyA tails for enrichment, our first attempts at RNA-seq were 95% ribosomal. Combining partially successful double-stranded nuclease (DSN) treatment with massive sequencing depth we were able to get fairly high coverage of the transcriptome. Here’s where Ron Ammar, a graduate student supervised by me, Guri Giaever and Gary Bader stepped in and turned my laboratory adventures into a wonderful story. Ron mapped the reads from our nucleosome samples to the reference genome and found what to my eyes looked like a yeast nucleosome map only at half scale.

This was a pleasant surprise and one we did not take for granted given the high CG content of the genome (65%). We then turned to isolating RNA. Without polyA tails for enrichment, our first attempts at RNA-seq were 95% ribosomal. Combining partially successful double-stranded nuclease (DSN) treatment with massive sequencing depth we were able to get fairly high coverage of the transcriptome. Here’s where Ron Ammar, a graduate student supervised by me, Guri Giaever and Gary Bader stepped in and turned my laboratory adventures into a wonderful story. Ron mapped the reads from our nucleosome samples to the reference genome and found what to my eyes looked like a yeast nucleosome map only at half scale.

Here were well-ordered arrays in the gene bodies and nucleosome depleted regions at the ends of genes. The Haloferax genome is a model of streamlining and as a consequence, intergenic regions are tiny and hard to define. With little published data to guide the definition of archea promoters and terminators the transcriptome map saved us. Ron focused on the primary chromosome in Haloferax and hand curated each transcription start and stop site based on the RNA-seq data. This is when we realized we had something interesting. Here were nucleosome depleted promoters and nucleosome depleted terminators and when we constructed an average-o-gram of all the nucleosome signatures for each promoter on the main chromosome, it looked like this….

The take home

The data strongly suggested that archae chromatin is organized in a matter very similar to eukaryotes. And further, the correlation between gene expression and nucleosome positioning, particularly with respect to the +1 and -1 nucleosomes was conserved. This conservation begs some interesting speculation. According to Koonin and colleagues the common ancestor of eukaryotes and archea predates the evolutionary split that gave rise to euryarchael and crenarchael lineages. Both of these branches have bona fide nucleosomes, therefore it would seem parsimonious to assume that the ancestor of these two branches also organized its genome into chromatin with anucleosomal scaffold. The similarities between the chomatin in archaea and eukaryotes, and the correlation between nucleosome occupancy and gene expression in archaea raise the interesting evolutionary possibility that the initial function of nucleosomes and chromatin formation might have been to regulate gene expression rather than for packaging of DNA. This is consistent with two decades of research that has shown that there is an extraordinarily complex relationship between the structure of chromatin and the process of gene expression. It also jives with in vitro observations that yeast H3/H4 tetramers can support robust transcription, while H2A/H2B tetramers cannot.

It is possible, therefore, that as the first eukaryotes evolved, nucleosomes and chromatin started to further compact their DNA into nuclei, which among other things, helped to prevent DNA damage, and that this subsequently enabled early eukaryotes to flourish. This observation is so exciting to me because it brings up so many questions that we can actually address such as- if there are nucleosomes comprised of histones, where are the histone chaperones? And further- despite the conventional wisdom that archael nucleosomes are not post translationally modified- this remains to be confirmed (or denied) experimentally. If conventional wisdom is correct and archea histones are not post countries post-translational and modified, then when did this innovation arise? There are more than enough questions to keep the lab buzzing!

Publishing the paper

Because I truly believed that this result “would be of general interest to a broad readership” we prepared a report for Science which was returned to us within 48 hours. The turnaround from Nature was even faster. I had received emails from eLIFE several months previously, and after reading the promotional materials and the surrounding press, we took our chances s at eLIFE and hoped for the best. The best is exactly what we got. Within a few days the editors emailed that the manuscript was out for peer review and four weeks later we received the reviews. They were unique. They outlined required, non-negotiable revisions (including a complete resequencing of the genome after MNase digestion but without prior cross-linking) but contained no gray areas and required no mind-reading. With all hands on deck and we resubmitted the manuscript in four weeks and were overjoyed with its acceptance. Of course with N=1, combined with a positive outcome it’s hard to be anything but extremely positive about this new journal. But I think the optimism is defendable- the reviews were transparent, and the criticisms made it a better paper. The editorial staff was supportive gave us the opportunity to take the first stab at drafting the digest which accompanies the manuscript.

NOTE ADDED BY JONATHAN EISEN. A preprint of the paper is available here. Thanks to the eLife staff for helping us out with this and encouraging posting prior to formally going live on the eLife site.

What’s next and what’s in the freezer

This work represents the Haloferax reference condition, with asynchronously growing cells in rich, high-salt media. We recently collected samples of log phase cultures exposed to several environmental stresses and samples from lag, log and stationary phases of growth to chart archael nucleosome dynamics. We are also refining a home-made ribosomal depletion protocol to make constructing complementary transcriptome maps considerably cheaper. Finally, it is exciting to contemplate a consortium effort to create a systematic, barcoded set of Haloferax deletion (or disruption) mutants for systematic functional studies.

Mille grazie to Jonathan E. for inspiring me to looking at understudied microbes and for encouraging me to walk the walk with respect to publishing in open access forums. And for letting me share my thoughts as a guest on his blog

|

| The tree of life from Haloferax’s perspective Artwork by Trine Giaever |

Story behind the Paper: Functional biogeography of ocean microbes

Guest Post by Russell Neches, a PhD Student in my lab and Co-Author on a new paper in PLoS One. Some minor edits by me.

For this installment of the Story Behind the Paper, I’m going to discuss a paper we recently published in which we investigated the geographic distribution of protein function among the world’s oceans. The paper, Functional Biogeography of Ocean Microbes Revealed through Non-Negative Matrix Factorization, came out in PLOS ONE in September, and was a collaboration among Xingpeng Jiang (McMaster, now at Drexel), Morgan Langille (UC Davis, now at Dalhousie), myself (UC Davis), Marie Elliot (McMaster), Simon Levin (Princeton), Jonathan Eisen (my adviser, UC Davis), Joshua Weitz (Georgia Tech) and Jonathan Dushoff (McMaster).

|

sample A

|

sample B

|

sample C

|

…

|

|

|

factor 1

|

3.3

|

5.1

|

0.3

|

…

|

|

factor 2

|

1.1

|

9.3

|

0.1

|

…

|

|

factor 3

|

17.1

|

32.0

|

93.1

|

…

|

|

…

|

…

|

…

|

…

|

…

|

Which factors are important? Which differences among samples are important? There are a variety of mathematical tools that can help distill these tables into something perhaps more tractable to interpretation. One way or another, all of these tools work by decomposing the data into vectors and projecting them into a lower dimensional space, much the way object casts a shadow onto a surface.

|

|

The idea is to find a projection that highlights an important feature of the original data. For example, the projection of the fire hydrant onto the pavement highlights its bilateral symmetry.

So, projections are very useful. Many people have a favorite projection, and like to apply the same one to every bunch of data they encounter. This is better than just staring at the raw data, but different data and different effects lend themselves to different projections. It would be better if people generalized their thinking a little bit.

When you make a projection, you really have three choices. First, you have to choose how the data fits into the original space. There is more than one valid way of thinking about this. You could think about it as arranging the elements into vectors, or deciding what “reshuffling” operations are allowed. Then, you have to choose what kind of projection you want to make. Usually people stick with some flavor of linear transformation. Last, you have to choose the space you want to make your projection into. What dimensions should it have? What relationship should it have with the original space? How should it be oriented?

In the photograph of the fire hydrant, the original data (the fire hydrant) is embedded in a three dimensional space, and projected onto the ground (the lower dimensional space) by the sunlight by casting a shadow. The ground happens to be roughly orthogonal to the fire hydrant, and the sunlight happens to fall from a certain angle. But perhaps this is not the ideal projection. Maybe we’d get a more informative projection if we put a vertical screen behind the fire hydrant, and used a floodlight? Then we’d be doing the same transformation on the same representation of the data, but into a space with a different orientation. Suppose we could make the fire hydrant semi-transparent, we placed it inside a tube-shaped screen, and illuminated the fire hydrant from within? Then we’d be using a different representation of the original data, and we’d be doing a non-linear projection into an entirely different space with a different relationship with the original space. Cool, huh?

It’s important to think generally when choosing a projection. When you start trying to tease some meaning out of a big data set, the choice of principal component analysis, or k-means clustering, or canonical correlation analysis, or support vector machines, has important implications for what you will (or won’t) be able to see.

How we started this collaboration: a DARPA project named FunBio

Between 2005 and 2011, DARPA had a program humbly named The Fundamental Laws of Biology (FunBio). The idea was to foster collaborations among mathematicians, experimental biologists, physicists, and theoretical biologists — many of whom already bridged the gap between modeling and experiment. Simon Levin was the PI of the project and Benjamin Mann was the program officer. The group was large enough to have a number of subgroups that included theorists and empiricists, including a group focused on ecology. Jonathan Eisen was the empiricist for microbial ecology, and was very interested in the binning problem for metagenomics; that is, classifying reads, usually by taxonomy. Conversations in and out of the program facilitated the parallel development of two methods in this area: LikelyBin (led by Andrey Kislyuk and Joshua Weitz with contributions from Srijak Bhatnagar and Jonathan Dushoff) and CompostBin (led by Sourav Chatterji and Jonathan Eisen with contributions from collaborators). At this stage, the focus was more on methods than biological discoveries.

The binning problem highlights some fascinating computational and biological questions, but as the program developed, the group began to tilt in direction of biological problems. For example, Simon Levin was interested in the question: Could we identify certain parts of the ocean that are enriched for markers of social behavior?

One of the key figures in any field guide is a ecosystem map. These maps are the starting point from which a researcher can orient themselves when studying an ecosystem by placing their observations in context.

|

|

|

In the discussions that followed, we discussed how to describe the functional and taxonomic diversity in a community as revealed via metagenomics; that is, how do we describe, identify and categorize ecosystems and associated function? In order to answer this question, we had to confront a difficult issue: how to quantify and analyze metagenomic profile data.

Metagenomic profile data: making sense of complexity at the microbe scale

Metagenomics is perhaps the most pervasive cause of the proliferation of giant tables of data that now beset biology. These tables may represent the proportion of taxa at different sites, e.g., as measured across a transect using effective taxonomic units as proxies for distinct taxa. Among these giant tables, one of the challenges that has been brought to light is that there can be a great deal of gene content variability among individuals of an individual taxa. As a consequence, obtaining the taxonomic identities of organisms in an ecosystem is not sufficient to characterize the biological functions present in that community. Furthermore, ecologists have long known that there are often many organisms that could potentially occupy a particular ecological niche. Thus, using taxonomy as a proxy for function can lead to trouble in two different ways; the organism you’ve found might be doing something very different from what it usually does, and second, the absence of an organism that usually performs a particular function does not necessarily imply the absence of that function. So, it’s rather important to look directly at the genes in the ecosystem, rather than taking proxies. You can see where this is going, I’m sure: Metagenomics, the cure for the problems raised by metagenomics!

When investigating these ecological problems, it is easy to take for granted the ability to distinguish one type of environment from another. After all, if you were to wander from a desert to a jungle, or from forest to tundra, you can tell just by looking around what kind of ecosystem you are in (at least approximately). Or, if the ecosystems themselves are new to you, it should at least be possible to notice when one has stepped from one into another. However, there is a strong anthropic bias operating here, because not all ecosystems are visible on humans scales. So, how do you distinguish one ecosystem from another if you can’t see either?

One way is to look at the taxa present, but that works best if you are already somewhat familiar with that ecosystem. Another way is to look at the general properties of the ecosystem. With microbial ecosystems, we can look at predicted gene functions. Once again, this line of reasoning points to metagenomics.

We wanted to use a projection method that avoids drawing hard boundaries, reasoning that hard boundaries can lead to misleading results due to over-specification. Moreover, in doing so Jonathan Dushoff advocated for a method that had the benefits of “positivity”, i.e., the projection would be done in a space where the components and their weights were positive, consistent with the data, and which would help the interpretability of our results. This is the central reason why we wanted to use an alternative to PCA. The method Jonathan Dushoff suggested was Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). This choice led to a number of debates and discussions, in part, because NMF is not a “standard” method (yet). Though, it has seen increasing use within computational biology: http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pcbi.1000029. It is worth talking about these issues to help contextualize the results we did find.

The Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) approach to projection

The conceptual idea underlying NMF (and a few other dimensional reduction methods) is a projection that allows entities to exist in multiple categories. This turns out to be quite important for handling corner cases. If you’ve ever tried to build a library, you’ve probably encountered this problem. For example, you’ve probably created categories like Jazz, Blues, Rock, Classical and Hip Hop. Inevitably, you find artists who don’t fit into the scheme. Does Porgy and Bess go into Jazz or Opera? Does the soundtrack for Rent go under Musicals or Rock? What the heck is Phantom of the Opera anyway? If your music library is organized around a hierarchy of folders, this can be a real headache, and either results either in sacrificing information by arbitrarily choosing one legitimate classification over another, or in creating artistically meaningless hybrid categories.

This problem can be avoided by relaxing the requirement that each item must belong to exactly one category. For music libraries, this is usually accomplished by representing categories as attribute tags, and allowing items to have more than one tag. Thus, Porgy and Bess can carry the tags Opera, Jazz and Soundtrack. This is more informative and less brittle.

NMF accomplishes this by decomposing large matrices into smaller matrices with non-negative components. These decompositions often do a better job at clustering data than eigenvector based methods for the same reason that tags often work better for organizing music than folders. In ecology, the metabolic profile of a site could be represented as a linear combination of site profiles, and the site profile of a taxonomic group could be represented as a linear combination of taxonomic profiles. When we’ve tried this, we have found that although many sites, taxa and Pfams have profiles close to these “canonical” profiles, many are obviously intermediate combinations. That is to say, they have characteristics that belong to more than one classification, just as Porgy and Bess can be placed in both Jazz and Opera categories with high confidence. Because the loading coefficients within NMF are non-negative (and often sparse), they are easy to interpret as representing the relative contributions of profiles.

What makes NMF really different from other dimensional reduction methods is that these category “tags” are positive assignments only. Eigenvector methods tend to give both positive and negative assignments to categories. This would be like annotating Anarchy in the U.K. by the Sex Pistols with the “Classical” tag and a score of negative one, because Anarchy in the U.K. does not sound very much like Frédéric Chopin’s Tristesse or Franz Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor. While this could be a perfectly reasonable classification, it is conceptually very difficult to wrap one’s mind around concepts like non-Punk, anti-Jazz or un-Hip-Hop. From an epistemological point of view, it is preferable to define things by what they are, rather than by what they are not.

To give you an idea of what this looks like when applied to ecological data, it is illustrative to see how the Pfams we found in the Global Ocean Survey cluster with one another using NMF, PCA and direct similarity:

While PCA seems to over-constrain the problem and direct similarity seems to under-constrain the problem, NMF clustering results in five or six clearly identifiable clusters. We also found that within each of these clusters one type of annotated function tended to dominate, allowing us to infer broad categories for each cluster: Signalling, Photosystem, Phage, and two clusters of proteins with distinct but unknown functions. Finally – in practice, PCA is often combined with k-means clustering as a means to classify each site and function into a single category. Likewise, NMF can be used with downstream filters to interpret the projection in a “hard” or “exclusive” manner. We wanted to avoid these types of approaches.

Indeed, some of us had already had some success using NMF to find a lower-dimensional representation of these high-dimensional matrices. In 2011, Xingpeng Jiang, Joshua Weitz and Jonathan Dushoff published a paper in JMB describing a NMF-based framework for analyzing metagenomic read matrices. In particular, they introduced a method for choosing the factorization degree in the presence of overlap, and applied spectral-reordering techniques to NMF-based similarity matrices to aid in visualization. They also showed a way to robustly identify the appropriate factorization degree that can disentangle overlapping contributions in metagenomics data sets.

While we note the advantages of NMF, we should note it comes with caveats. For example, the projection is non-unique and the dimensionality of the projection must be chosen carefully. To find out how we addressed these issues, read on!

Using NMF as a tool to project and understand metagenomic functional profile data

We analyzed the relative abundance of microbial functions as observed in metagenomic data taken from the Global Ocean Survey dataset. The choice of GOS was motivated by our interest in ocean ecosystems and by the relative richness of metadata and information on the GOS sites that could be leveraged in the course of our analysis. In order to analyze microbial function, we restricted ourself to the analysis of reads that could be mapped to Pfams. Hence, the matrices have columns which denote sampling sites, and rows which denote distinct Pfams. The values in the cell denotes the relative number of Pfams matches at that site, where we normalize so that the sum of values in a column equals 1. In total, we ended up mapping more than six million reads into a 8214 x 45 matrix.

We then utilized NMF tools for analyzing metagenomic profile matrices, and developed new methods (such as a novel approach to determining the optimal rank), in order to decompose our very large 8214 x 45 profile matrix into a set of 5 components. This projection is the key to our analysis, in that it highlights the most of the meaningful variation and provides a means to quantify that variation. We spent a lot of time talking among ourselves, and then later with our editors and reviewers, about the best way to explain how this method works. Here is our best effort from the Results section that explains what these components represent :

Each component is associated with a “functional profile” describing the average relative abundance of each Pfam in the component, and with a “site profile”, describing how strongly the component is represented at each site.

Such a projection does not exclusively cluster sites and functions together. We discovered five functional types, but we are not claiming that any of these five functional types are exclusive to any particular set of sites. This is a key distinction from concepts like enterotypes.

What we did find is that of these five components, three of them had an enrichment for Pfams whose ontology was often identified with signalling, phage, and photosystem function, respectively. Moreover, these components tended to be found in different locations, but not exclusively so. Hence, our results suggest that sampling locations had a suite of functions that often co-occurred there together.

We also found that many Pfams with unknown functions (DUFs, in Pfam parlance) clustered strongly with well-annotated Pfams. These are tantalizing clues that could perhaps lead to discovery of the function of large numbers currently unknown proteins. Furthermore, it occurred to us that a larger data set with richer metadata might perhaps indicate the function of proteins belonging to clusters dominated by DUFs. Unfortunately, we did not have time to fully pursue this line of investigation, and so, with a wistful sigh, we kept in the the basic idea, with more opportunities to consider this in the future. We also did a number of other analyses, including analyzing the variation in function with respect to potential drivers, such as geographic distance and environmental “distance”. This is all described in the PLoS ONE paper.

So, without re-keying the whole paper, we hope this story-behind-the-story gives a broader view of our intentions and background in developing this project. The reality is that we still don’t know the mechanisms by which components might emerge, and we would still like to know where this this component-view for ecosystem function will lead. Nevertheless, we hope that alternatives to exclusive clustering will be useful in future efforts to understand complex microbial communities.

Full Citation: Jiang X, Langille MGI, Neches RY, Elliot M, Levin SA, et al. (2012) Functional Biogeography of Ocean Microbes Revealed through Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. PLoS ONE 7(9): e43866. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043866.

Adaptation and Convergence in Regulatory Systems, guest post by David Pollock

Below is another in my series on “The Story Behind the Paper” with guest posts from authors of open access papers of relevance to this blog. Today’s post comes from David Pollock in Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Colorado School of Medicine. Note – I went to graduate school with David and he is a long time friend. This is why he apparently feels okay to call me Jon even though I go by Jonathan. I have modified his text only to format it. Plus I added some figures from his paper.

Explanation

This is a guest blog post about a paper of mine just published in Genome Biology and Evolution, “SP transcription factor paralogs and DNA bindingsites coevolve and adaptively converge in mammals and birds“, and it amounts to my first attempt at an un-press release. You can tell it’s not a press release because I’m writing this about a week after the paper came out. This guest blog is coming about because I released an announcement about the paper to a few friends, and credited my old buddy Jon Eisen with having inspired me to move towards avoiding press releases. And I sure wouldn’t want this paper to be named in the same breath as the now infamous arsenic bacteria and Encode project press releases (although I note that a recent paper from my lab estimates that the human genome is at least 2/3 derived from repetitive sequence); also see posts by Michael Eisen and by Larry Moran. I had the vague idea that maybe Jon, Ed Yong, Carl Zimmer, or some other famous blogger would be so inspired by the move (and the fundamental coolness of the paper) that they would quickly write up a thoughtful interpretive summary for general audiences. Jon, however, being much to smart for my own good, suggested that I should write it up as a guest blog instead. So, here I am. At least I got Jon to agree to edit it.

Okay then, why do I think adaptation and convergence in regulatory systems is cool and important? Well, first because I think a lot of important changes in evolution have to have come about through regulatory evolution, and yet there are huge gaps in our knowledge of how this change might happen. And I say this as someone who has spent most of his career studying (and still believing in the importance of) sequence evolution. Second, a lot of people seem to think that evolution of whole regulatory systems should be hard, because there are so many interactions that would need to change at the same time. Remember, transcription factors can interact with hundreds of different binding sites to regulate hundreds of different proteins. It makes sense that evolution of such a system should be hard. In this paper, I think we go a long way towards demonstrating that this intuitive sense is wrong, that functional evolution of regulatory systems can happen quite easily, that it has happened in a system with around a thousand functional binding sites, and that some of the details of how it happens are really interesting.

Aside from promoting the science, the other reason I want to blog about this paper is that I think it is a great demonstration of how fun and how diverse science can be. To support its points, it brings in many different types of evidence, from genomics to population genetics to protein structure prediction. It is also a good example of using only publicly available data, plus a lot of novel analysis, to see something interesting that was just sitting there. I think there must be a lot more stories like that. All of that Encode data, for example, is bound to have some interesting undiscovered stories, even with 30 papers already published. The most fun part, though, which I don’t think I can fully recreate without jumping up and down in front of you, was just the thrill of discovery, and the thrill of having so many predictions fall into place with data from so many different sources.

I don’t recall another project where we would say so many times, “well, if that is the explanation, then let’s look at this other thing,” and bam!, we look at the other thing and it fits in too. It started with Ken Yokoyama, the first author, walking into the lab having just published some pretty good evidence that the preference for the SP1-associated binding site (the GC-box) was newly evolved in the ancestor to eutherian mammals. Well, if that’s true, there ought to be a change in the SP1 protein sequence that can explain it. Sure enough, there is, and SP1 is a very conserved protein that doesn’t change a lot. Hmm, we have more sequences now, let’s look to see if preferences changed anywhere else on the phylogenetic tree. Yes, in birds. Well, there ought to be a change in bird SP1 that can explain that; sure enough, there is, and it’s at the homologous position in the protein. Looking good, but is it in the right place in the protein? Yes, in the right domain (zinc finger 2, or zf2), right behind the alpha helix that binds the nucleotide for which the preference changed. And before you ask, Ken ran a protein structure prediction algorithm on the amino acid replacements in SP1, and the predicted functional replacements in bird and mammal are predicted to bend the protein right at the point where it binds the nucleotide at which the preference changed. You might then ask if this amino acid replacement does anything to the binding function, and the answer again is “yes”. This time, though, we were able to rely on existing functional studies, which showed that human SP1 binds 3x better to the GC-box binding site than it does to the ancestral GA-box (more on this below).

The coup de grace on this residue position as the source of convergent functional changes, though, came with consideration of the other transcription factors that interact in this regulatory system (that is, they bind to the same binding sites to modify transcription). If there was a functional change in the transcription factor, driving modified changes in the binding sites, then it seems that this should affect the other transcription factors in the system. It could have been hard to figure anything out about these other transcription factors, but luckily they consist of SP3 and SP4, two paralogs of SP1. This means that they are ancient duplicates of ancestral SP proteins, they share a great deal of conserved sequence with SP1, and they bind with similar affinities to the SP1 binding consensus. And they have not just one or two, but between the two proteins, in birds and mammals, at least eight convergent amino acid replacements at the homologous position that putatively modified binding in SP1. And the substitution that occurs is the same replacement that occurred in bird SP1. Based on sequences from jawed fish and frogs, this position was almost completely conserved in the SP3 and SP4 paralogs for 360 or 450 million years of evolution. The convergent changes all occurred in only the last 100 million years or less of eutherian and bird lineages. We believe that the simplest interpretation is that, over tens of millions of years, a functional replacement occurred at the SP1 protein, adaptively driving hundreds of SP1 binding sites to convert from ancestral GA-boxes to derived GC-boxes, and that this then drove the same functional replacement in coregulatory paralogs SP3 and SP4.

Timing and a mechanism

Two questions often comes up at this point, “how do we know the order of these events?” The simplest piece of evidence for the order of events comes from the order of fixation of substitutions. The amino acid substitutions in SP1 are fixed in all eutherian mammals and all birds, indicating that they occurred on the branches leading to these taxon groups. The increase in GC-boxes occurred over time at different loci, mostly on the branch leading to eutherian mammals and on the branches immediately after that split the most ancient eutherian mammal groups. The replacements in SP3 and SP4 occurred later in the evolution of eutherian mammals and birds, and did not occur in all lineages. One might be able to come up with complicated scenarios whereby changes in some SP1 binding sites occurred first, driving the fixation of the SP1 replacement, followed by further selected changes in other SP1 binding sites, but we think our hypothesis is simpler.

Other pieces of evidence also come into play. The question about the order of events can be rephrased as a question of whether neutral forces, such as changes in mutation rates at binding sites, could have altered the frequency of the alternative binding sites, with SP1 (and then SP3 and SP4) playing functional catch-up to better match the new binding site frequencies. It seems to us that such a model would predict that the binding sites would have changed irrespective to the function of the proteins that they regulate. (As an aside here, we note that our binding site data set is best described not as a definitive set of SP1-regulated promoters, but as a set that is highly enriched in functional SP1 binding sites. We don’t trust binding site function predictions, and the putative binding sites inclusively considered were those that had either the ancestral GA-box or the derived GC-box in the functionally relevant region prior to the transcription start site. Such sites are highly enriched for categories of genes known to be under SP1 control.) But the binding sites that shift from GA-boxes to GC-boxes are even further enriched for categories of genes under SP1 control. This is not compatible with the neutral mutational shift model, but is compatible with the idea that the subset of our sites for which SP1 regulation is most important are the ones that were most likely to adaptively shift box type when the SP1 with altered function became more frequent.

The mutational driver model also predicts a simple shift in frequencies driven by mutation. For example, GA-boxes might tend to mutate into GC-boxes, and conversely, GC-boxes might tend to be conserved and not mutate to GA-boxes. What I haven’t told you yet, though, is that the excess GC-boxes do not tend to be produced by mutation from GA-boxes, but rather they tend to be produced as de novo mutations from non-SP1 box sequences. They are produced by a wide variety of mutations from a wide variety of different sequences that are slightly different from the canonical SP1 binding sites. Furthermore, the GC-boxes appear in a burst of birth early in eutherian evolution, but the GA-boxes don’t disappear in a burst at the same time. Rather, they simply fade away slowly over time in lineages that have evolved GC-boxes. It is not clear to us that this can be explained using a mutation model, but it is easily explained by a model in which the SP1 replacement has adaptively driven hundreds of binding site convergent events. This is then followed by the slow mutational degradation of the GA-boxes, which don’t matter so much to function anymore. It is also worth mentioning that the GC box preference doesn’t seem to correlate with GC content, as several fish lineages are just as high in GC content as humans, but do not have the GC-box preference.

The observed pattern of binding site evolution is also predicted by a model we developed to determine if the evolution of transcription factors and their binding sites could be explained in a population genetics framework. We asked, what is a possible mechanism by which these changes might occur? At the beginning of this post, I noted that a lot of people seem to think that evolution of complex multi-genic regulatory systems should be hard. We reasoned, though, that if the beneficial effects of a newly evolved binding interaction were dominant or semi-dominant (that is, the beneficial effects in the heterozygote were at least partly visible to selection), then it might be possible for evolution to be achieved through a transition period in which both the transcription factor and its cognate binding sites were polymorphic.

We developed both a deterministic and a stochastic model, and found that, indeed, even small (nearly neutral) selective benefits per locus can drive the entire system to fixation. What happens is that as long as there are some binding loci with the new binding box in the system, then a new variant of SP1 with a preference for the new binding box, and an associated small selective benefit, will at first rapidly increase in frequency. It won’t immediately fix though, but rather will maintain a temporary steady state, kept down in frequency by the deleterious effects that new variant homozygotes would have with the large number of binding loci that are homozygous for the ancestral binding box. Once it has reached this steady state, it exerts selective pressure on all the binding loci to increase the frequencies of the new binding boxes at each locus. Much more slowly then, the frequency of the new transcription factor variant increases, in step with the frequencies of new binding boxes at all the binding loci.

Although our studies do not prove that our population genetics model is the exact mechanism for adaptive changes in SP1, it provides proof of concept that it is not difficult for such a mechanism to exist.

At the broader level, this paper shows that small selective benefits can drive the evolution of complex regulatory systems (in diploids, at least; sorry to leave out the micro folks, Jon). Furthermore, it demonstrates, we believe convincingly, that adaptation has driven the evolution of the SP1 regulatory system, driving convergent evolution at many hundreds of promoters, and in SP3 and SP4. It thus strongly counters prevailing notions that such evolution is hard. We hope that this work (along with other work of this kind) will drive others to further pursue the broad questions in regulatory evolution. Are the details of the SP1 system common to other regulatory systems?

A particularly important question, which we did not focus on here, is whether the evolution we have described involves only static maintenance of the status quo in terms of which genes are regulated. One has to wonder, though, whether if it is easy to evolve a static regulatory system, that it is not therefore easier than previously believed to modify regulatory connections in a complex regulatory system. There are hints of such changes here, in that genes that may have gained novel SP1 regulation (that is, gained a GC-box when they did not have the ancestral GA-box) tend to be enriched in certain GO categories (see Table 2 in the paper).

For SP1, it will be interesting to see if good stories can be developed for to explain why this adaptation should have occurred specifically in birds and eutherian mammals. The ideal story should include both a biophysical mechanism, and a physiology-based mechanism, such as the possibility that warm-bloodedness played a role. Both of these avenues promise to be complicated, if addressed properly. For example, we believe that it will be more meaningful if a biophysical mechanism can address the need for specificity as well as strength of binding, perhaps by utilizing next-generation sequencing approaches to measure affinities for all relevant binding site mutations (see, among others, our recent paper on this topic, Pollock et al., 2011). Are there interactive roles for selection on transcription factor concentration as well as efficiency and selectivity? What trade-offs exist among binding efficiency and binding site duplication? Do different types of regulatory connections evolve differently? These are all great questions for future research.

Addendum

I’ll try to add further comments if questions or issues come up. I’m particularly interested to see how this non-press release guest log post works as an experiment to promote the paper and the work. I also hope it will promote Ken Yokoyama’s career (he’s now at Illinois, and will probably be looking for an academic job in the next year or two). He did an awesomely diverse amount of work on this, learning how to work in totally new areas for him, such as population genetics, birth/death models, and protein structure prediction. He dove into these areas unhesitatingly to pursue the logical scientific questions, developed novel analyses, and did a great job. This paper represents a fundamental contribution and a fantastic advertisement for Ken’s abilities.

Guest post: Story Behind the Paper by Joshua Weitz on Neutral Theory of Genome Evolution

I am very pleased to have another in my “Story behind the paper” series of guest posts. This one is from my friend and colleague Josh Weitz from Georgia Tech regarding a recent paper of his in BMC Genomics. As I have said before – if you have published an open access paper on a topic related to this blog and want to do a similar type of guest post let me know …

—————————————-

A guest blog by Joshua Weitz, School of Biology and Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology

Summary This is a short, well sort-of-short, story of the making of our paper: “A neutral theory of genome evolution and the frequency distribution of genes” recently published in BMC Genomics. I like the story-behind-the-paper concept because it helps to shed light on what really happens as papers move from ideas to completion. It’s something we talk about in group meetings but it’s nice to contribute an entry in this type of forum. I am also reminded in writing this blog entry just how long science can take, even when, at least in this case, it was relatively fast.

The pre-history The story behind this paper began when my former PhD student, Andrey Kislyuk (who is now a Software Engineer at DNAnexus) approached me in October 2009 with a paper by Herve Tettelin and colleagues. He had read the paper in a class organized by Nicholas Bergman (now at NBACC). The Tettelin paper is a classic, and deservedly so. It unified discussions of gene variation between genomes of highly similar isolates by estimating the total size of the pan and core genome within multiple sequenced isolates of the pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae.

However, there was one issue that we felt could be improved: how does one extrapolate the number of genes in a population (the pan genome) and the number of genes that are found in all individuals in the population (the core genome) based on sample data alone? Species definitions notwithstanding, Andrey felt that estimates depended on details of the alignment process utilized to define when two genes were grouped together. Hence, he wanted to evaluate the sensitivity of core and pan geonme predictions to changes in alignment rules. However, it became clear that something deeper was at stake. We teamed up with Bart Haegeman, who was on an extended visit in my group from his INRIA group in Montpellier, to evaluate whether it was even possible to quantitatively predict pan and core genome sizes. We concluded that pan and core genome size estimates were far more problematic than had been acknowledged. In fact, we concluded that they depended sensitively on estimating the number of rare genes and rare genomes, respectively. The basic idea can be encapsulated in this figure:

The top panels show gene frequency distributions for two synthetically generated species. Species A has a substantially smaller pan genome and a substantially larger core genome than does Species B. However, when one synthetically generates a sample set of dozens, even hundreds of genomes, then the rare genes and genomes that correspond to differences in pan and core genome size, do not end up changing the sample rarefaction curves (seen at the bottom, where the green and blue symbols overlap). Hence, extrapolation to the community size will not necessarily be able to accurately estimate the size of the pan and core genome, nor even which is larger!

As an alternative, we proposed a metric we termed “genomic fluidity” which captures the dissimilarity of genomes when comparing their gene composition.

The quantitative value of genomic fluidity of the population can be estimated robustly from the sample. Moreover, even if the quantitative value depends on gene alignment parameters, its relative order is robust. All of this work is described in our paper in BMC Genomics from 2011: Genomic fluidity: an integrative view of gene diversity within microbial populations.

However, as we were midway through our genomic fluidity paper, it occurred to us that there was one key element of this story that merited further investigation. We had termed our metric “genomic fluidity” because it provided information on the degree to which genomes were “fluid“, i.e., comprised of different sets of genes. The notion of fluidity also implies a dynamic, i.e., a mechanism by which genes move. Hence, I came up with a very minimal proposal for a model that could explain differences in genomic fluidity. As it turns out, it can explain a lot more.

A null model: getting the basic concepts together

In Spring 2010, I began to explore a minimal, population-genetics style model which incorporated a key feature of genomic assays, that the gene composition of genomes differs substantially, even between taxonomically similar isolates. Hence, I thought it would be worthwhile to analyze a model in which the total number of individuals in the population was fixed at N, and each individual had exactly M genes. Bart and I started analyzing this together. My initial proposal was a very simple model that included three components: reproduction, mutation and gene transfer. In a reproduction step, a random individual would be selected, removed and then replaced with one of the remaining N-1 individuals. Hence, this is exactly analogous to a Moran step in a standard neutral model. At the time, what we termed mutation was actually representative of an uptake event, in which a random genome was selected, one of its genes was removed, and then replaced with a new gene, not found in any other of the genomes. Finally, we considered a gene transfer step in which two genomes would be selected at random, and one gene from a given genome would be copied over to the second genome, removing one of the previous genes. The model, with only birth-death (on left) and mutation (on right), which is what we eventually focused on for this first paper, can be depicted as follows:

We proceeded based on our physics and theoretical ecology backgrounds, by writing down master equations for genomic fluidity as a function of all three events. It is apparent that reproduction decreases genomic fluidity on average, because after a reproduction event, two genomes have exactly the same set of genes. Likewise, gene transfer (in the original formulation) also decreases genomic fluidity on average, but the decrease is smaller by a factor of 1/M, because only one gene is transferred. Finally, mutation increases genomic fluidity on average, because a mutation event occurring at a gene which had before occurred in more than one genome, introduces a new singleton gene in the population, hence increasing dissimilarity. The model was simple, based on physical principles, was analytically tractable, at least for average quantities like genomic fluidity, and moreover it had the right tension. It considered a mechanism for fluidity to increase and two mechanisms for fluidity to decrease. Hence, we thought this might provide a basis for thinking about how relative rates of birth-death, transfer and uptake might be identified from fluidity. As it turns out, many combinations of such parameters lead to the same value of fluidity. This is common in models, and is often referred to as an identifiability problem. However, the model could predict other things, which made it much more interesting.

The making of the paper

The key moment when the basic model, described above, began to take shape as a paper occurred when we began to think about all the data that we were not including in our initial genomic fluidity analysis. Most prominently, we were not considering the frequency at which genes occurred amongst different genomes. In fact, gene frequency distributions had already attracted attention. A gene frequency distribution summarizes the number of genes that appear in exactly k genomes. The frequency with which a gene appears is generally thought to imply something about its function, e.g., “Comprising the pan-genome are the core complement of genes common to all members of a species and a dispensable or accessory genome that is present in at leastbone but not all members of a species.” (Laing et al., BMC Bioinformatics 2011). The emphasis is mine. But does one need to invoke selection, either implicitly or explicitly, to explain differences in gene frequency?

As it turns out, gene frequency distributions end up having a U-shape, such that many genes appear in 1 or a few genomes, many in all genomes (or nearly all), and relatively few occur at intermediate levels. We had extracted such gene frequency distributions from our limited dataset of ~100 genomes over 6 species. Here is what they look like:

And, when we began to think more about our model, we realized that the tension that led to different values of genomic fluidity also generated the right sort of tension corresponding to U-shaped gene frequency distributions. On the one-hand, mutations (e.g., uptake of new genes from the environment) would contribute to shifting the distribution to the left-hand-side of the U-shape. On the other hand, birth-death would contribute to shifting the distribution to the right-hand side of the U-shape. Gene transfer between genomes would also shift the distribution to the right. Hence, it seemed that for a given set of rates, it might be possible to generate reasonable fits to empirical data that would generate a U-shape. In doing so, that would mean that the U-shape was not nearly as informative as had been thought. In fact, the U-shape could be anticipated from a neutral model in which one need not invoke selection. This is an important point as it came back to haunt us in our first round of review.

So, let me be clear: I do think that genes matter to the fitness of an organism and that if you delete/replace certain genes you will find this can have mild to severe to lethal costs (and occasional benefits). However, our point in developing this model was to try and create a baseline null model, in the spirit of neutral theories of population genetics, that would be able to reproduce as much of the data with as few parameters as possible. Doing so would then help identify what features of gene compositional variation could be used as a means to identify the signatures of adaptation and selection. Perhaps this point does not even need to be stated, but obviously not everyone sees it the same way. In fact, Eugene Koonin has made a similar argument in his nice paper, Are there laws of adaptive evolution: “the null hypothesis is that any observed pattern is first assumed to be the result of non-selective, stochastic processes, and only once this assumption is falsified, should one start to explore adaptive scenarios”. I really like this quote, even if I don’t always follow this rule (perhaps I should). It’s just so tempting to explore adaptive scenarios first, but it doesn’t make it right.

At that point, we began extending the model in a few directions. The major innovation was to formally map our model onto the infinitely many alleles model of population genetics, so that we could formally solve our model using the methods of coalescent theory for both cases of finite population sizes and for exponentially growing population sizes. Bart led the charge on the analytics and here’s an example of the fits from the exponentially growing model (the x-axis is the number of genomes):

At that point, we had a model, solutions, fits to data, and a message. We solicited a number of pre-reviews from colleagues who helped us improve the presentation (thank you for your help!). So, we tried to publish it.

Trying to publish the paper

We tried to publish this paper in two outlets before finding its home in BMC Genomics. First, we submitted the article to PNAS using their new PNAS Plus format. We submitted the paper in June 2011 and were rejected with an invitation to resubmit in July 2011. One reviewer liked the paper, apparently a lot: “I very much like the assumption of neutrality, and I think this provocative idea deserves publication.” The same reviewer gave a number of useful and critical suggestions for improving the manuscript. Another reviewer had a very strong negative reaction to the paper. Here was the central concern: “I feel that the authors’ conclusion that the processes shaping gene content in bacteria and primarily neutral are significantly false, and potentially confusing to readers who do not appreciate the lack of a good fit between predictions and data, and who do not realise that the U-shaped distributions observed would be expected under models where it is selection that determines gene number.” There was no disagreement over the method or the analysis. The disagreement was one of what our message was.

I still am not sure how this confusion arose, because throughout our first submission and our final published version, we were clear that the point of the manuscript was to show that the U-shape of gene frequency distributions provide less information than might have been thought/expected about selection. They are relatively easy to fit with a suite of null models. Again, Koonin’s quote is very apt here, but at some basic level, we had an impasse over a philosophy of the type of science we were doing. Moreover, although it is clear that non-neutral processes are important, I would argue that it is also incorrect to presume that all genes are non-neutral. There’s lots of evidence that many transferred genes have little to no effect on fitness. We revised the paper, including and solving alternative models with fixed and flexible core genomes, again showing that U-shapes are rather generic in this class of models. We argued our point, but the editor sided with the negative review, rejecting our paper in November after resubmission in September, with the same split amongst the reviewers.

Hence, we resubmitted the paper to Genome Biology, which rejected it at the editorial level after a few week delay without much of an explanation, and at that point, we decided to return to BMC Genomics, which we felt had been a good home for our first paper in this area and would likely make a good home for the follow-up. A colleague once said that there should be an r-index, where r is the number of rejections a paper received before ultimate acceptance. He argued that r-indices of 0 were likely not good (something about if you don’t fall, then you’re not trying) and an r-index of 10 was probably not good either. I wonder what’s right or wrong. But I’ll take an r of 2 in this case, especially because I felt that the PNAS review process really helped to make the paper better even if it was ultimately rejected. And, by submitting to Genome Biology, we were able to move quickly to another journal in the same BMC consortia.

Upcoming plans

Bart Haegeman and I continue to work on this problem, from both the theory and bioinformatics side. I find this problem incredibly fulfilling. It turns out that there are many features of the model that we still have not fully investigated. In addition, calculating gene frequency distributions involves a number of algorithmic challenges to scale-up to large datasets. We are building a platform to help, to some extent, but are looking for collaborators who have specific algorithmic interests in these types of problems. We are also in discussions with biologists who want to utilize these types of analysis to solve particular problems, e.g., how can the analysis of gene frequency distributions be made more informative with respect to understanding the role of genes in evolution and the importance of genes to fitness. I realize there are more of such models out there tackling other problems in quantitative population genomics (we cite many of them in our BMC Genomics paper), including some in the same area of understanding the core/pan genome and gene frequency distributions. I look forward to learning from and contributing to these studies.

Story behind the paper guest post on "Resolving the ortholog conjecture"

This is another in my ongoing “Story behind the paper series”. This one is from Christophe Dessimoz on a new paper he is an author on in PLoS Computational Biology that is near and dear to my heart.

See below for more. I am trying to post this from Yosemite National Park without full computer access so I hope the images come through. If not I will fix in a few days.

……………..

I’d like to thank Jonathan for the opportunity to tell the story behind our paper, which was just published in PLoS Computational Biology. In this work, we corroborated the “ortholog conjecture”—the widespread but little tested notion that orthologs tend to be functionally more conserved than paralogs.

I’d also like to explore more general issues, including the pitfalls of statistical analyses on highly heterogeneous data such as the Gene Ontology, and the pivotal role of peer-reviewers.

Like many others in computational biology, this project started as a quick analysis that was meant to take “just a few hours” but ended up keeping us busy for several years…

The ortholog conjecture and alternative hypotheses

The ortholog conjecture states that on average and for similar levels of sequence divergence, genes that started diverging through speciation (“orthologs”) are more similar in function than genes that started diverging through duplication (“paralogs”). This is based on the idea that gene duplication is a driving force behind function innovation. Intuitively, this makes sense because the extra copy arising through duplication should provide the freedom to evolve new function. This is the conventional dogma.

Alternatively, for similar levels of sequence divergence, there might not be any particular difference between orthologs and paralogs. It is the simplest explanation (per Ockham’s razor), and it also makes sense if the function of a gene is mainly determined by its protein sequence (let’s just consider one product per gene). Following this hypothesis, we might expect considerable correlation between sequence and function similarity.

But these are by no means the only two possible hypotheses. Notably, Nehrt and colleagues saw higher function conservation among within-species homologs than between-species homologs, which prompted them to conclude: “the most important aspect of functional similarity is not sequence similarity, but rather contextual similarity”. If the environment (“the context”) is indeed the primary evolutionary driving force, it is not unreasonable to speculate that within-species paralogs could evolve in a correlated manner, and thus be functionally more similar than their between-species counterparts.

Why bother testing these hypotheses?

Testing these hypotheses is important not only for better understanding gene function evolution in general, but it also has practical implications. The vast majority of gene function annotations (98% of Gene Ontology annotations) are propagated computationally from experimental data on a handful of model organisms, often using models based on these hypotheses.

How our work started

Our project was born during a break at the 10th anniversary meeting of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics in September 2008. I was telling Marc Robinson-Rechavi (University of Lausanne) about my work with Adrian Altenhoff on orthology benchmarking (as it happens, another paper edited by Jonathan!), which had used function similarity as a surrogate measure for orthology. We had implicitly assumed that the ortholog conjecture was true—a fact that Marc zeroed in on. He was quite sceptical of the ortholog conjecture, and around this time, together with his graduate student Romain Studer, he published an opinion in Trends in Genetics unambiguously entitled “How confident can we be that orthologs are similar, but paralogs differ?” (self-archived preprint). So, having all that data on hand, we flipped our analysis on its head and set out to compare the average Gene Ontology (GO) annotation similarity of orthologs vs. paralogs. Little did we think that this analysis would keep us busy for over 3 years!

First attempt

It only took a few weeks to obtain our first results. But we were very puzzled. As Nehrt et al. would later publish, we observed that within-species paralogs tended to be functionally more conserved than orthologs. At first we were very sceptical. After all, Marc had been leaning toward the uniform ortholog/paralog hypothesis, and I had expected the ortholog conjecture to hold. We started controlling for all sorts of potential sources of biases and structure in the data (e.g. source of ortholog/paralog predictions, function and sequence similarity measures, variation among species clades). A year into the project, our supplementary materials had grown to a 67-page PDF chock-full of plots! The initial observation held under all conditions. By then, we were starting to feel that our results were not artefactual and that it was time to communicate our results. (We were also running out of ideas for additional controls and were hoping that peer-reviewers might help!)

Rejections

We tried to publish the paper in a top-tier journal, but our manuscript was rejected prior to peer-review. I found it frustrating that although the work was deemed important, they rejected it prior to review over an alleged technical deficiency. In my view, technical assessments should be deferred to the peer-review process, when referees have the time to scrutinise the details of a manuscript.

Genome Research sent our manuscript out for peer-review, and we received one critical, but insightful report. The referee contended that our results were due to species-specific factors, which arise because “paralogs in the same species tend to be ‘handled’ together, by experimenters and annotators”. The argument built on one example which we had discussed in the paper: S. cerevisiae Cdc10/Cdc12 and S. pombe Spn2/Spn4 are paralogs inside each species, while Cdc10/Spn2 and Cdc12/Spn4 are the respective pairs of orthologs. The Gene Ontology annotations for the orthologs were very different, while the annotations of theparalogs were very similar. The reviewer looked at the source articles indetail, and noticed that “the functional divergence between these genes is more apparent than real”. Both pairs of paralogs were components of theseptin ring. The differences in annotation appeared to be due to differences in the experiments done and in the way they were transcribed. The reviewer stated:

“A single paper will often examine the phenotype of several paralogs within onespecies, resulting in one paper, which is presumably processed by one GO annotator at one time. In contrast, phenotypes of orthologs in different species almost always come from different papers, via different annotation teams.”

Authorship effect: an easily overlooked bias

At first, it was tempting to just dismiss the criticism. After all, as Roger Brinner put it, “the plural of anecdote is not data.” More importantly, we had tried to address several potential species-specific biases, such as uneven annotation frequencies among species (e.g. due to developmental genes being predominantly studied in C. elegans). And we had been cautious in our conclusions, suggesting that our results might be due to an as yet unknown confounder in the Gene Ontology dataset (remember that we had run out of ideas?). So the referee was not telling us anything we did not know.

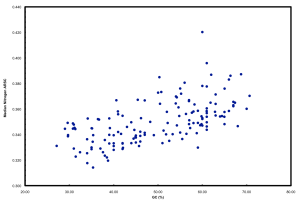

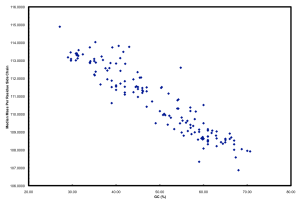

Or was (s)he? Stimulated by the metaphor of same-species paralogs being “handled” together, we decided to investigate whether common authorship might correlate in any way with function annotation similarity. Here’s what we observed:

The similarity of function annotations from a common paper is much higher than otherwise! Even if we restrict ourselves to annotations from different papers, but with at least one author in common, the similarity of functional annotations is still considerably higher than with papers without a common author.

Simpson’s Paradox

In itself, the authorship effect is not necessarily a problem: if annotations between orthologs and paralogs were similarly distributed among the different types, differences due to authorship effects would average out. The problem here is that paralogs are one order of magnitude more likely to be annotated by the same lab than orthologs. This gives rise to “Simpson’s paradox”: paralogs can appear to be functionally more similar than orthologs just because paralogs are much more likely to be studied by the same people.