I am very excited about today’s post. It is the first in what I hope will be many – posts from authors of interesting papers describing the “Story behind the paper“. I write extensive detailed posts about my papers and also have tried to interview others about their papers if they are relevant to this blog. But Matthew Hahn approached me recently about the possibility of him writing up some details on his recent paper on the functions of orthologs vs. paralogs. So I said “sure” and set up a guest account for him to write up his comments and details of the paper.

For those of you who do not know, Matt is on the faculty at U. Indiana. He was a post doc at UC Davis so I have a particular bias in favor of him. But his recent paper has generated some controversy (I posted some links about it here). So it is great to get some more detail from him. In addition, I note, I am also using this approach to try and teach people how easy it is to write a blog post by getting them guest accounts on Blogger and letting them write up something with links, pictures, etc. So hopefully we can get more scientists blogging too.

Anyway – without any further ado – here is Matt’s post:

———————————————————————–

Following Jonathan’s excellent

example of how explaining the history of a project helps to illuminate how the process of science actually happens, I thought I’d start by giving a bit of history behind our study, and the paper that we recently published in PLoS Computational Biology (

http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002073). And then I’ll address the critics…

How this all got started

It all started a bit more than three years ago, in the summer of 2008. Pedja (as Predrag Radivojac is known to friends) was giving a talk to a group of us on protein function prediction that he also presented as a tutorial at the Automated Function Prediction SIG at ISMB 2008. Pedja and I had already collaborated on a small

project involving the evolution of phosphoryation sites, but I really had no idea about his work on function prediction, and little idea in general about how function prediction was done. Reviewing different ways to accomplish transfer-by-similarity, he eventually got around to evolutionary (phylogenomic) approaches. Here is what I remember of this specific exchange during his talk:

Pedja: …and of course these methods only use orthologs for prediction, because orthologs have more similar functions than do paralogs.

me (from audience): Who says?

Pedja: Umm, you say. I mean, the evolutionary biologists say.

me: No, we don’t. I don’t know of any data that says any such thing.

Pedja: Whatever, Matt. We’ll talk about this later.

Well, we did talk about it later, and it turned out that although this claim is made in tons of papers, there is basically no data to support it. In the best cases a real example of one gene family will be cited, but there are very few of these. In the worst cases, the authors will just cite some random paper about gene duplicates (or Fitch’s original

paper defining orthologs and paralogs). Of course I agree that patterns of

sequence evolution might lead you to conclude this relationship was true, but there was no experimental data.In fact, as we say in our paper, rarely did anyone recognize that this claim needed to be tested, or even that it was a claim that could be tested. At the time Eugene Koonin was the only person to say this: “The validity of the conjecture on functional equivalency of orthologs is crucial for reliable annotation of newly sequenced genomes and, more generally, for the progress of functional genomics. The huge majority of genes in the sequenced genomes will never be studied experimentally, so for most genomes transfer of functional information between orthologs is the only means of detailed functional characterization” (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16285863). I really liked the way that Eugene had said this, and started to refer to the idea that orthologs were more functionally similar than paralogs as the “ortholog conjecture.” So to be clear: I completely made up this phrase, but used the most evocative word from the Koonin paper.

Luckily for Pedja and me we had just gotten a small internal grant to work on genome annotation and we had an incoming master’s student (Nathan Nehrt) who was willing to work on a project intending to test the ortholog conjecture.

Interlude: the crappy state of things in the study of the evolution of function

In order to test anything about how function evolves between orthologs and paralogs—or between any genes—one of course needs some kind of data on gene function in multiple species. And this turns out to be a big problem.

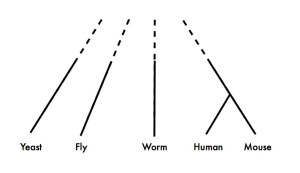

Because, as Koonin says in the earlier quote, the vast majority of experimental data comes from a very few species, and these species are not exactly closely related. Here is an approximate phylogeny of the major eukaryotic model organisms:

It’s obvious from this figure that if you need both 1) lots of functional data from two species, and 2) a pretty good idea of exactly what the homologous relationships are between the genes you’re studying, you’re going to have to study human and mouse.

This is actually a pretty bleak picture for people who study molecular evolution (as I do). While we have tons and tons of sequence data both within and between species, and a very good idea about how these sequences evolve, and fancy models with which to analyze these sequences…we know next to diddly-squat about general patterns relating these sequence differences to functional differences. There are lots of interesting things to be gleaned from studies of sequence evolution, but it really would be nice to know something about the relationship between sequence and function.

What we found

What exactly does the ortholog conjecture predict? In my mind, at least, it predicts something like this:

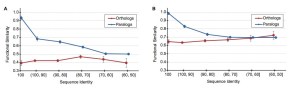

In this completely fictitious graph the relationship between protein function and sequence similarity is a declining one, only it declines faster for paralogs than it does for orthologs. Also, just possibly, gene duplicates start out with slightly diverged function the minute they appear. Anyway, those were our predictions.

But here is what we found (Figure 1 in Nehrt et al. 2011):

(Panel A uses the Biological Process ontology and panel B uses the Molecular Function ontology.)

There are really two different, equally surprising results here. First, there is no relationship between sequence divergence and functional divergence for orthologs (among 2,579 one-to-one orthologs between human and mouse). Absolutely none—it’s a straight horizontal line. Second, there is a relationship for paralogs (among 21,771 comparisons), exactly as we predicted there would be. So according to our results, paralogs actually have more conserved function than do orthologs. Our interpretation of the data was that the most important determinant of function was the organismal context in which a gene/protein found itself: given the same amount of sequence divergence, two proteins in the same organism would be more functionally similar. For orthologs, this means that the sequence divergence of our target gene was not the most important thing, but rather the sum total of divergence in all of the genes that contribute to its cellular context. Which is why all the orthologs have on average similar functional divergence—they are all exactly the same age and hence have approximately the same levels of divergence in these interactors (in this case sequence divergence for paralogs is a much better indicator of their splitting time).

Without going through every result in the paper and our interpretation of every result, suffice it to say that after about a year-and-a-half of working on this (around February 2010), we were satisfied that we had something we were willing to submit. I even seem to remember showing the above figure to Jonathan on a visit to UC-Davis! So we did submit the paper, first to PNAS and then, after rejection, to PLoS Computational Biology, where it was rejected again.

The content of the reviews was approximately the same at both journals. Basically, people were not convinced of our results mostly because the functional relationships were all based on data in the Gene Ontology database. To be specific, the functional data we used came from experiments conducted in 12,204 different papers. We didn’t use any predicted functions, only functions assigned using experimental data. And we did A LOT of work to try to eliminate problems that might have affected our results, including repeating the main analysis using only GO terms common to both the human and mouse datasets. But there can still be bias hidden within these functional assignments because someone always has to interpret the experiment—to say that a yeast two-hybrid experiment means that a gene has function X. And because of these biases, people weren’t buying it.

To get a measure of functional similarity that did not depend on the interpretation of any experiments, we decided to repeat the entire analysis using microarray data, using the correlation in expression levels across 25 tissues as the measure of functional similarity. By this time Nathan was graduating and moving on to Maricel Kann’s lab as a research programmer, so we recruited one of Pedja’s Ph.D. students, Wyatt Clark, to pick up where Nathan had left off. (Wyatt had actually been a student in my undergraduate Evolution course a few years earlier, so we figured he knew something…) After repeating all of the GO-based analyses himself—always better to double-check, right?—Wyatt got all of the microarray data in order and produced this figure (Figure 4 in Nehrt et al. 2011):

So a year after we first submitted a paper, we submitted a new version to PLoS CB including the array analysis, and this was enough to convince the reviewers that our results were not merely due to some strange bias in GO.

The fallout, and some responses

First, let me say that I had some idea that this would be a controversial-ish paper, and that we’d get at least some blowback. For about the first 20 versions of the manuscript (including some submitted versions) I put the words “ortholog conjecture” in quotes in the title, never an endearing move. (Pedja finally convinced me to take them out of the latest submissions.) But I also thought people would be happier that an untested assumption had finally been tested—and we have definitely gotten some positive feedback along these lines, including several groups that told us they have data that support our findings. By coincidence my lab had another paper come out the same week as this one (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21636278), and I mistakenly thought it would generate much more attention. I still think the biological importance of the results in that one are much greater than the ortholog conjecture results, but either because we didn’t publish in an open-access journal (Jonathan is always right) or simply because the function-prediction community is more active on the interweb tubes, there have been a surprising number of critical responses (partially collected here:

http://phylogenomics.blogspot.com/2011/09/some-links-on-ortholog-conjecture-paper.html). So here are some responses to general critiques.

The ortholog conjecture says only that orthologs are similar.

Okay, this one is a bit unfair, as only one person has said this. The real problem here is that Michael Galperin seems to have deeply misunderstood what we mean by the ortholog conjecture.

According to him the ortholog conjecture is “the assumption that orthologs (genes with a common origin that were vertically inherited from the same gene in the last common ancestor of the host organisms) typically retain the same function or have closely related ones.” Umm, no. In fact, if you really think this is what the ortholog conjecture says, then our results support it—human and mouse orthologs do typically have closely related functions. But we are explicitly testing for a difference between orthologs and paralogs, not whether or not orthologs retain any functions. At no point did we say (or even hint) that orthologs should not be used for functional prediction. The whole point of our analysis and conclusions is that we should stop ignoring paralogs, which would give us a ton more data to use for the prediction of functions.

The assignments of orthology and paralogy are incorrect.

This is an easy one: we did in fact get the definitions of in- and out-paralogs correct (and laid them out in Figure S1). According to Sonnhammer and Koonin: “Our definition of ‘outparalogs’ is: paralogs in the given lineage that evolved by gene duplications that happened before the radiation (speciation) event” (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12446146). For the purposes of our study, this means that outparalogs are defined as any paralogs that diverged before the speciation event between human and mouse and inparalogs diverged after this speciation event. Outparalogs do not indicate only paralogs in two different species, though by necessity in our dataset inparalogs are only found in the same species (all in human or all in mouse). Therefore, with respect to our conclusion that the most important determinant of function is which genome you are found in (i.e. context), it wouldn’t matter if we had incorrect gene trees: we would never confuse two genes in the same species (either inparalogs or some of the outparalogs) with two genes in different species (all orthologs and the remaining outparalogs).

You should have inferred functions yourselves

This is a fair suggestion, and not having enough time to annotate functions for 40,000 proteins would be a pretty weak excuse for doing good science. Instead…I’ll just say that it turns out professional curators are much better at assigning functions than even the original study authors (see

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20829821). Curators have a much broader view of the whole set of terms available in any ontology, and a much more consistent idea of how to apply these terms. My favorite line from the above cited article: “…because of the relatively low accuracy of the authors’ submissions, the use of authors’ annotations did not result in saving of curators’ time…”

GO is not appropriate for this analysis because it is biased.

This is the most frustrating criticism of our study, if only because it’s partly true: GO is biased. In our paper we actually detail several of these biases, including the observation that the same set of authors will give two proteins more-similar functions than will two different sets of authors. We tried very hard to attempt to control for these biases, though of course one cannot account for all of them. The most uncharitable part of this critique, however, has to be the fact that people conveniently forgot to say that our array analysis was completely distinct from the GO-based analysis (though it has its own issues), and that Burkhard Rost’s analysis of protein-protein interaction (

http://www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020079) was also completely free of any bias in GO and was consistent with all of our results.

More annoying than this, you’d think from some of the critiques of GO that it was some sort of fly-by-night operation that no one should ever depend on. I mean, c’mon—there are human curators and human experimenters and of course they’re all biased so badly one could never compare functions between proteins much less between species. What were we thinking? (Only that the original GO paper has been cited >7000 times.) Funnily enough, at several points during the course of this work Pedja suggested—only half-jokingly—that we should just assume the ortholog conjecture was correct and write a paper about how GO must be wrong. Seriously, though: one would think from the excuses people came up with for the problems inherent in GO that we should simply stop using it to, you know, predict function in other species. And we were applying it to two relatively closely related mammals, one of which is explicitly a model for the other.

What next?

Our paper laid out several explicit hypotheses about the evolution of function that arose from our findings. Unfortunately, testing any of these hypotheses will require a ton more functional data, in more than one species. I know there are multiple groups working to collect these sorts of labor-intensive datasets, and Pedja and I are thinking about doing it ourselves (with collaborators, of course!). Massive datasets that reveal protein function will always be a lot harder to collect than sequence data, especially ones free from biases.

So let’s get to it…

—————————

Note – Toni Gabaldón was trying to post a detailed response but Blogger kept cutting him off with a character limit. So I have posted his response below.

I appreciate the effort by Matthew Hahnn on explaining the story behind his paper on the so-called “Ortholog conjecture” and on facing some of the criticism. This paper attracted my interest as that of many others that work on or just use orthology. For instance it was chosen by one of my postdocs for our “Journal Club” meeting. And it was discussed during our last “Quest for Orthologs” meeting in Cambridge. I think is raising a necessary discussion and therefore I think is a good paper. This does not mean that I fully agree with the interpretation and conclusions ;-). I hope to modestly contribute to this debate with the following post.

I think one of the causes that this paper has caused so much debate is that the conclusions seem to challenge common practice (inferring function from orthologs), and could be interpreted as the need of changing the strategies of genome annotation. I think, however, that one should interpret carefully these results before start annotating based on paralogous proteins. As I will discuss below one of the problems is that we need to agree in what is the conjecture to then agree in how to test it. I see three main points that can be a source of confusion: i) the issue of what is actually stated by this conjecture, ii) the issue of annotation, and iii) the issue of time

1) What is the “ortholog conjecture”?

Or in other terms, when should we expect orthologs to be more likely to share function than paralogs?. Always? Of course not. All of us would agree that two recently duplicated paralogs are likely to be more similar in function than two distant orthologs, so it is obvious that the conjecture is not simply “orthologs are more similar in function than paralogs”. In reality the expectation that orthologs are more likely to be similar in function than paralogs, as least this is how I interpret it, is directly related to the effect that duplication have on functional divergence. If gene duplication has some effect on functional divergence (even in not 100% of the cases), then, given all other things equal (divergence time, story of speciation/duplication events – except fpr the duplication defining the orthologs) one would expect orthologs to be more likely to conserve function.

I think this complexity is not well considered (by many authors, in general). Hahn refeers to the famous review of orthology by Koonin (2005) as the source for the term “ortholog conjecture”. However, In that paper this conjecture is discussed always within the context of genes accross two particular species, whether in Hahn’s paper it is taken as well to other contexts. Thus, the proper context in which to test this conjecture is only between orthologs and between-species paralogs. As we can see, Red and purple lines in Hahn paper in figure2 do not show any clear difference.

Secondly, Koonin was very cautions in his paper, stating that he was referring to “equivalent functions” and not exactly the same “function”, correctly implying that the functional contexts would be different in the two different species. This brings me to the next point.

ii) annotation

If the expectation of functional conservation of orthologs refers to a given pair of species, then it makes no sense to test that expectation between paralogs within the same species and orthologs in different species. We were interested in this issue and it took us some effort to control for this “species” influence on the comparison, if you are interested you can read our paper on divergence of expression profiles between orthologs and paralogs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21515902)

As Hahn founds, and it was anticipated by Koonin in that review, there is a huge influence of the “species context”, a big constraint of what fraction of the function is shared. Indeed I think is the dominant signal in Hahn’s paper. Why is that? One possibility is that the functional context determines the function, I agree. However, we should not discard biases in how different communities working around a model species define processes and function, also the type of experiments that are usually done. For instance experimental inference from KO mutants might be common from mouse, but I guess is not the case in humans (!!). I think this may be having a big influence and might even be the dominant signal in Hahns paper.

Finally function has many levels and I expect subfunctionalization mostly affect lower levels (i.e. more specific). Biases may also

exist in the level of annotation between species or between families of different size (contributing more or less to the orthologs/paralogs class).

Microarray data are less likely to be subject to biases (although some may exist), at least they should be expected to be free of “human interpretation biases” and so Hahn and colleaguies did well, in my opinion, of testing that dataset. It is important to note that for microarrays and for orthologs and between-species paralogs (which I think is the right frame for testing the conjecture) ortholgs are more likely to share an expression context. This is compatible to what we found in the paper mentioned above, and compatible with the orthology conjecture as stated by koonin (accross species)

iii) time

Finally, one aspect which I think is fundamental is the notion of “divergence time”. Since paralogs can emerge at different time-scales they are composed by a heterogeneous set of protein pairs. Most of comparisons of orthologs and paralogs (Hahn’s as well) use sequence divergence as a proxy of time. However this is only a poor estimate, specially when duplications (as in here) are involved (we explored this issue in the past: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21075746). This means that for a given divergence time paralogs may have larger sequence divergence than orthologs at the same divergence time, or otherwise (if gene conversion is playing a role). Is the conjecture based on sequence divergence or on divergence time?, I think the initial sense of using orthology to annotate accross species is based on the notion of comparing things at the same evolutionary distance. Thus basing our conclusions on divergence times might not be the proper way of doing it.

CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSAL FOR RE-STATEMENT

To conclude, and with the intention of going beyond this particular paper,

I would finish by saying that the key to the problem lies on how we interpret the so-called “ortholog conjecture” or how are our expectations on how function evolves. What I get from re-reading Eugene Koonin’s paper and how I am using that “assumption” in my day-to-day work is the following:

“Orthologs in two given species are more likely to share equivalent functions than paralogs between these two species”

Therefore the notion of “accross the same pair of species” is important and thus only part of the comparisons made by Hahn and colleagues could directly test this. Looking at the microarray and between-species comparisons data, the conjecture may even hold true!!

I, however, do think that the conjecture as stated above is limited and does not capture the complexity of orthology relationships. Indeed us, and many other researchers, are tuning the confidence of the orthology-based annotation based on whether the orthologs are one-to-one, one-to-many or many-to-many, even when orthologs are “super-orthologs” (with no duplication event in the lineages separating the two orthologs).

Since, the underlying assumption of the ortholog conjecture is that duplication may (not necessarily always) promote functional shifts, then many-to-many orthology relationships will tend to include orthologous pairs with different functions.

Thus I would re-state the conjecture (or expectation) as follows:

“In the absence of additional duplication events in the lineages separating them, two orthologous genes from two given species are more likely to share equivalent functions than two paralogs between these two species”

This would be a more conservative expectation, which is closer to the current use of orthology-based annotation that tends to identify one-to-one orthologs, rather than any type.

When duplications start appearing in subsequent lineages thus creating one- or many-to-many orthology relationships, the situation is less clear. Following the assumption that duplications may promote functional divergence. Then one could expand the conjecture by “the more duplications in the evolutionary history separating two genes, the lower the expectation that these two genes would share equivalent functions”.

I wrote this contribution on the fly, and surely there are ways of expressing this in more appropriate terms. In any case I hope I made clear the idea that the conjecture emerges from the notion of duplications causing functional shifts and that our expectations will be clearer if expressed on those terms. This goes on the lines of what Jonathan Eisen mentioned on considering the whole phylogenetic story to annotate genes.

Under this perspective, the real important hypothesis is that “duplications tend promote functional shifts”, I think this is based on solid grounds and has been tested intensively in the past.

Cheers,

Toni Gabaldón

http://treevolution.blogspot.com

I wrote some questions up for Andrew Allen, one of the authors. I note I did this before my “new” system of inviting authors to write guest posts directly themselves. Not sure which approach is better but guest posts are certainly easier for me so I will probably do that more.

I wrote some questions up for Andrew Allen, one of the authors. I note I did this before my “new” system of inviting authors to write guest posts directly themselves. Not sure which approach is better but guest posts are certainly easier for me so I will probably do that more. I wrote some questions up for Andrew Allen, one of the authors. I note I did this before my “new” system of inviting authors to write guest posts directly themselves. Not sure which approach is better but guest posts are certainly easier for me so I will probably do that more.

I wrote some questions up for Andrew Allen, one of the authors. I note I did this before my “new” system of inviting authors to write guest posts directly themselves. Not sure which approach is better but guest posts are certainly easier for me so I will probably do that more.